Traditionel sydindisk lægekunst i området omkring Tranquebar

Kenneth G. Zysk, Ph.d, Dr. Phil, Institut for tværkulturelle og regionale studier, afdeling for Asien studier, Københavns universitet

- Projektet er finansieret af Bikubenfonden og har plads på Galathea3 ekspeditionen.

Dette projekt vil fokusere på den Indiske Siddha – lægevidenskabs historie og udvikling i Tamil Nadu og dens forhold til Ayurveda – lægevidenskaben.

Før muslimerne kom i det 10 århundrede e. kr., eksisterede der to fremherskende former for lægekunst i Indien: Ayuveda i Nordindien samt det centrale Indien og dele af Kerala i syd, og Siddha som hovedsageligt er fra Tamil Nadu. Begge har lange historier og bliver stadig praktiseret i deres respektive Indiske regioner.

Meget er skrevet omkring historien, udviklingen og praktiseringen af Ayurveda både på sanskrit og på hindi. Meget lidt vides derimod om Siddha fordi dens skrevne historie er begrænset og fordi viden om Siddah er blevet mundtligt overleveret fra lærer til student.

Ayurveda bruger balancen fra tre basale kropsvæsker til at diagnosticere: luft, galde og slim. Balancen bliver genoprettet og vedligeholdt ved en kombination af urter, mineraler, livsstil og til tider kirurgi. Siddha bruger derimod andre former for årsagslære, inklusiv puls- diagnosticering med flere. Kuren skabes primært af et system af medicinsk alkymi. Begge systemer hviler på en fundamental forståelse af forholdet imellem mennesker og deres miljø.

Tranquebar i Tamil Nadu er perfekt til undersøgelser i den Sydindiske tradition af Siddha.

Der findes allerede optegnelser, der detaljeret beretter om mødet mellem Siddha og dens praktiserende og de danske læger, som var tilknyttet Tranquebar. Ved at bruge denne information som udgangspunkt i disse informationer, vil et detaljeret studium af medicinens historie og praksis, samt den indflydelse den havde på både den vestlige medicin og på Ayurveda, blive gennemført.

Dette projekt vil arbejde tæt sammen med andre af initiativets projekter og vil involvere forskere og meddelere fra Indien, som vil sikre dataenes nøjagtighed og forskernes høje standart.

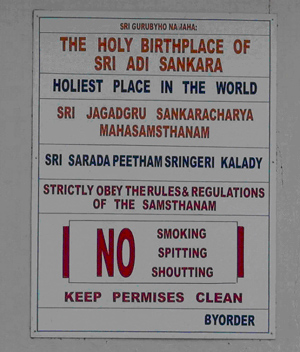

Foto: Ingrid Fihl Simonsen, aug. 2005